Mike Lapi is officially the Visiting Instructor of Animal Science for SUNY Cobleskill where he teaches all the meat processing courses through the federal inspection facility on campus. He went from accidental busboy to owning his own restaurant to building furniture and then teaching culinary classes before he took the helm of the meat processing program. We talked with Mike about his journey, his goals for the program and how he gets to keep cooking through events like Pig Island where he won an award for his homemade sausage served with charred slaw with house made fish sauce and pickled chanterelles.

Food Karma: Is it common for a university to have a meat processing facility?

Mike Lapi: No, we are the only SUNY institution that has a slaughterhouse on campus, and I’m pretty sure we’re one of the only few in the country that has a federal slaughterhouse that serves the outside community.

FK: How did you end up in this position?

ML: I actually went to school for fine art and ended up getting a job in a restaurant because I didn’t want to go home and milk cows again in the summer. I worked my way up in restaurants from being a dishwasher to head chef and ended up owning my own restaurant. When I owned my own restaurant, farmers started coming to me and offering whole animals. This was something new to me, and at that point I really gravitated towards utilizing everything I could from local sources. That was back in 2003, kind of before it was even a popular thing with restaurants. I started bringing back half pigs, whole pigs, cattle, poultry and learning how to break it down by hand with full utilization of everything that I was cutting for the restaurant. I taught myself how to break down carcasses and use every last piece of it.

In 2008 and 2009 when the economy crashed, we made a decision: we closed the restaurant, and I ended up moving back down to the Hudson Valley. My wife went back to school for nursing, and I ended up doing cabinetry for a couple years. Then I met Noah Sheetz around 2010 and I started working with the Chefs’ Consortium. He asked me if I wanted to cook at a culinary extravaganza event at SUNY Cobleskill. I’m from up there, why not?

So I did the event, and the department chair at the time asked me if I was interested in teaching in the fall. I had never even thought of being in education whatsoever in my entire life, that’s not what I had designed my life to do. But once I started doing it, there was immense gratification in seeing students learning and the level of excitement when they would see things like fresh pasta being made or something that they’ve never seen before and getting to know these students semester after semester. I still have contact with students I’ve known for almost ten years.

At that point I started adjuncting, and then within a year of adjuncting I got a call to come to the dean’s office. They wanted to have me design this farm to table class and also start teaching the meat processing classes. I was honest at that point, I said the farm to table thing is good but I’ve never processed meat in a federal establishment under processing guidelines. So I spent three semesters teaching meat processing in the culinary labs before the facility was finished in 2015. Once 2015 hit, I kind of migrated over across the road to do the meat processing in the new facility. At that point, I was just teaching the cutting classes. I learned how to adapt to production methods and then I started sitting in on the slaughter classes at the end of 2015. I spent a year on the slaughter floor every Monday, working there, learning, taking things in. Then at one point the instructor that was teaching the slaughter classes injured himself and didn’t come back. I did some more educational workshops on learning the slaughter practices.

In 2017, I took over all the slaughter classes and the meat processing classes and was still teaching the farm to table classes. Once I got really into what I was doing over there and really established, I actually was hired solely by animal science, so I wasn’t teaching culinary classes anymore just because the scope of everything that happens in that facility: I’m teaching classes, I’m working on production and all that. I’m only at the plant now. I teach all the slaughter classes, lectures, intro classes and upper level technique classes.

FK: You said you didn’t want to go home and milk cows, did you grow up on a farm?

ML: My grandfather owned a farm and he would always line me up with jobs when I was done with college. One winter break, I had come home and he would have gotten me a job. The four years through high school I worked at a neighboring farm until I graduated. It was kind of weird how I got picked up to work at restaurants. I was in the grocery store in New Paltz. I was looking at the help wanted board outside the Shop Rite, and a woman asked if I was looking for a job. I said yes, and she said come to this restaurant tomorrow in Woodstock, we want to give you a tour and see if you want to start. I started off bussing tables and soon migrated right into the kitchen.

FK: Were you always interested in food and cooking?

ML: It was definitely a huge part of my life. My grandmother was Sicilian, and we always had big, elaborate family meals and really good food. My mother was a really good cook. In my household, we didn’t have a lot of toys or things but we always ate good. We didn’t have a lot of money but we always had really good food, no matter what. Sometimes the phone would be shut off but we would have good food. We always ate well and we always ate together.

FK: Do you still get to do any professional cooking?

ML: I still do events whenever possible. I have a big event coming up this summer for the SALT group in Schoharie. There were floods there ten years ago and this group provides funds to reestablish the area. I’m going to be doing a big farm to table event with them. And I still do events all summer. I do the ASA event up in Washington County. The truth of the matter is all the events I’ve done in the last five years have all been outdoors. I haven’t been in a kitchen in a while.

FK: Who is buying the meat you process at the plant?

ML: That’s one of the best things about my job. We are processing meat for local farms. A lot of the farms that I’m cutting meat for are farms that I knew when I had the restaurant. That’s what I’m really proud of: I’m doing a community service and I’m completely involving students in this educational process but making them aware that they are part of something bigger than a classroom. We’re processing meat for the outside community and we’re doing the best we possibly can to make it presentable so they can sell it.

FK: So it goes back to the farms directly and they sell it?

ML: Yeah, we’re a normal federal establishment. We slaughter and process meat. It’s sold at farmers markets, retail, all kinds of different venues.

FK: In learning about the different parts of the animal, do you have a favorite cut that is not super popular?

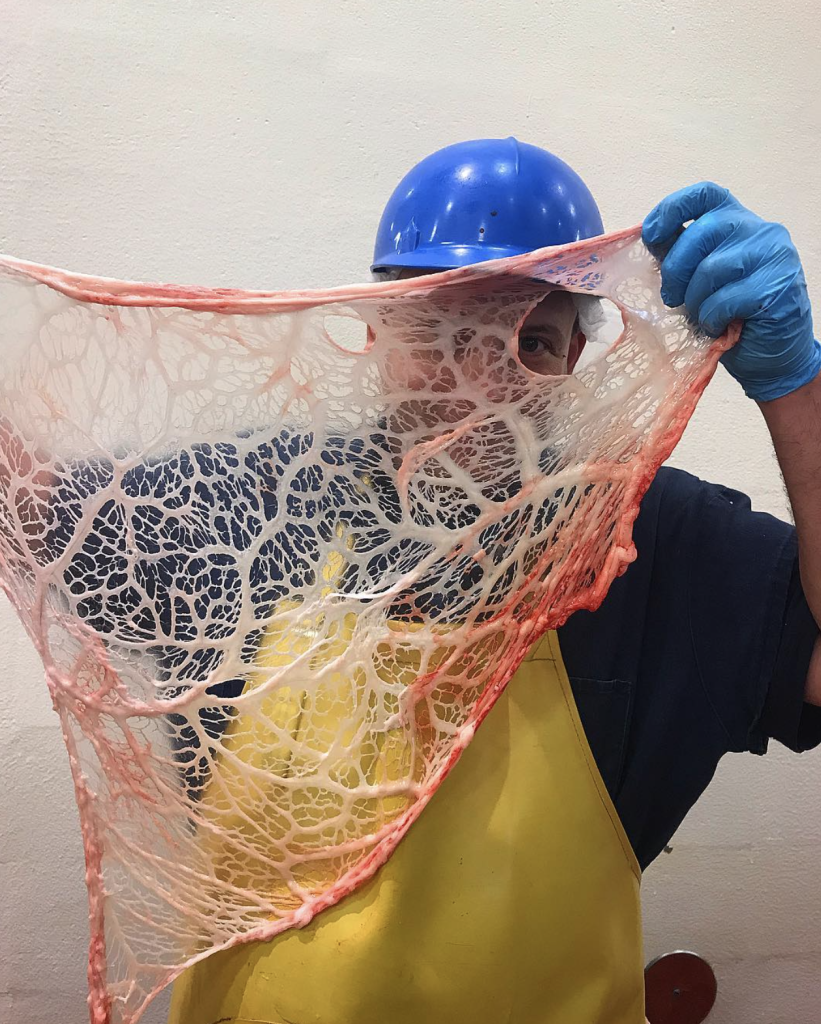

ML: Offal. I love educating customers on full utilization of their carcasses, like getting people to take back their organs, bones, everything like that.

FK: Are they receptive to that?

ML: Many are. One farm had such a great farmers market and had a twenty foot kitchen, I asked if they had tried making stock. He hadn’t, so I said give it a shot and see what happens. He came back to me a week later and said he ended up making like $600 off the stock.

FK: Are the other events you do similar to Pig Island?

ML: Yeah, a lot of them are big events, outside events, open fire events. I still love cooking but I love what I do now for sure.

FK: Since you started doing all this, have there been any major changes or trends?

ML: We’ve had such a demand for processing more, with all the meat shortages with covid and everything. People want to know where their food is coming from, so the response from the outside community is that people are going to farmers looking for local food. Then it’s just a backlash to the processors of how much they can take in. There’s a clear lack of meat processors in the country, so we’re starting to think outside the box of how we can train people, outside of just normal student access, to get into meat processing. We have a bunch of new programs that are going to be coming up in the fall.

FK: Do most of your students go on to do meat processing?

ML: No. For the most part, the normal student that I have doesn’t go on to be a meat processor. A lot of them go into being able to sell their meat through farmers’ markets. I kind of think of my role as kind of a dual purpose role: I’m not only teaching people how to be in the meat processing industry, but also I’m teaching young farmers how to sell their meat. I’m teaching people how to know what they’re selling and know what they’re cooking.

FK: Anything you’re excited about this year?

ML: I don’t know if I can really speak too much about it, but we’re actually in the process of creating new programs. We’ve been known for our summer program, so what we’re doing is building upon our summer program and starting to do more outside programming and extended, month long workshops. We have a lot of new stuff on the horizon that we’re developing, that we’re going to put out to the public to get more people into the industry and to train butchers.

FK: Tell us about your mushroom foraging.

ML: When I’m not working, I’m usually in the woods. Starting the end of April all the way up until November, any chance I get I’m out foraging mushrooms, plants, anything I can source locally to eat.

FK: How did you learn what was safe to eat?

ML: That was completely coincidental. Growing up, my father had brought home oyster mushrooms and puffballs and things like that, but one time I was walking through the forest and I walked over to these mushrooms. I knew I could visibly identify them just by looking at them, that’s a chanterelle. It just rang a bell. So I did all the research, I got all my field guides, I talked to experts and I got a positive ID on chanterelles. I had no idea they were in such abundance in my area. At that point, I researched and then I was walking behind my parents house one day and I was walking over what looked like a field of gold chanterelles. I had been walking over it my entire life without realizing it. I remember being a kid and walking in that stretch of woods and kicking mushrooms over. Now it’s this area I’ve been going to for 15 years, and every year it’s just loaded with chanterelles. Every year through research I find new species, and now I have it so I can identify probably 20-25 species. I’ve made vinegars from wild mushrooms, everything from preserving mushrooms to having them fresh all year long.

FK: Do you do this as a hobby for yourself and your family or do you teach other people too?

ML: My thing is I like sharing them. Whenever I have an abundance of mushrooms through the season, I share them with people who are interested. I try to put it out there as much as possible. It’s not monetary, it’s all about sharing with people and getting people exciting about it.

FK: Was covid good for mushrooms?

ML: Yeah, the last two years have been wonderful. It’s great being out in the woods, but having that when you can’t go anywhere else has been wonderful, but even the seasons have been really great.